How to Remain Focused Reading Books Paris Review

Don Mee Choi. Photograph: © SONG Got. Courtesy of Wave Books.

It's a cliché to say that reading transports yous, but in a yr in which I spent most of my days indoors, shuffling between my chamber and my living room, the books I read really were a lifeline, a portal to an outside world. In the weeks before New York shut down, I luxuriated in my subway reading, laughing aloud at Alma Mahler's antics in turn-of-the-century Vienna in Cate Haste's biography Passionate Spirit, savoring the deceptively calm sentences of Amina Cain's fabular Indelicacy, and texting photos of paragraphs from Abdellah Taïa'due south precipitous exploration of immigration, colonialism, and sexuality, A State for Dying (translated by Emma Ramadan), to everyone I knew. I spent an exhilarating calendar week attending a retrospective of the films of Angela Schanelec, a director whose piece of work frequently features writers, including her early on brusk I Stayed in Berlin All Summer, which contains a defence of fragmentation, of non making sense, that became something of a personal manifesto for my 2020. Nothing about my life or my country fabricated sense in one case March striking, and I stayed indoors reading Annie Ernaux'due south painful memoir well-nigh adolescence and abandonment, A Daughter's Story (translated by Alison Strayer); Fe Moon: An Anthology of Chinese Migrant Worker Verse (edited past Qin Xiaoyu and translated past Eleanor Goodman), which should be required reading for anyone who owns an Apple production or a fast-fashion clothing particular; and Marlen Haushofer'south particularly relevant dystopia, The Wall (translated past Shaun Whiteside). Kate Zambreno'south novel Drifts, which follows her narrator's attempts to end writing a novel, mirrored my own quarantined state of fitfulness, boredom, and bouts of obsession.

Equally the weather grew warmer, I kept thinking about the title story of Ho Sok Fong's Lake Like a Mirror (translated by Natascha Bruce) and the precision with which it portrays contemporary Malaysian politics. Grenade in Oral fissure: Some Poems of Miyó Vestrini (translated by Anne Boyer and Cassandra Gillig) electrified me, while Lyonel Trouillot's Street of Lost Footsteps (translated by Linda Coverdale) proved haunting. Elisa Gabbert'due south essay collection The Unreality of Retentiveness sent me down a one thousand Wikipedia rabbit holes. And I was delighted to read an early novel of Marie NDiaye'south, That Fourth dimension of Year (translated past Jordan Stump), with its questions of surveillance and insiders versus outsiders.

Autumn came, and in my insomnia leading up to the Nov election, I turned to Haytham El Wardany's The Book of Slumber (translated by Robin Moger), with its meditative look at slumber, revolution, and writing, and Elfriede Jelinek'due south incisive Trump-themed play, On the Royal Road: The Burgher Male monarch (translated by Gitta Honegger). The poems collected in Choi Seungja'due south Phone Bells Keep Ringing for Me (translated past Won-Chung Kim and Cathy Park Hong) shook me up with their raw criticisms of consumerism and honey, as did the essays on publishing and immigration in Dubravka Ugresic'southward The Historic period of Skin (translated by Ellen Elias-Bursać). Don Mee Choi'southward poetry collection DMZ Colony stayed with me long afterward it was over. And now it is somehow winter; now information technology is almost fourth dimension to flip the calendar forrad. In a yr marked by a pandemic, nothing made sense to me, least of all the passing of time.—Rhian Sasseen

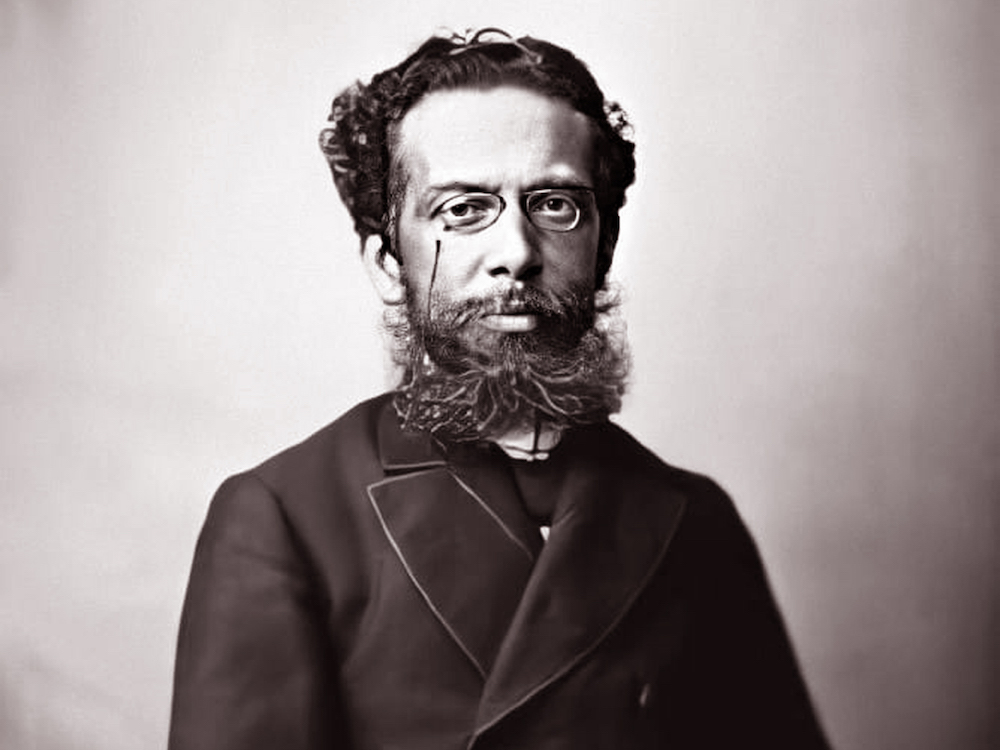

Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis. Photo: Marc Ferrez. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The clock and the calendar were both our allies and our enemies this year. I believe the books that stand out from my 2020 do and then in part because they take an involvement in this troubled relationship betwixt time and our finite experience of it. The outset of these is Machado de Assis's 1881 novel Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas, translated by William Grossman in 1952 as Epitaph of a Small Winner. (Two new translations of the book arrived this year: one by Flora Thomson-DeVeaux, the other by Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson, both bearing the title The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas.) In Grossman's rendering, the story is a picaresque retelling of Dante's Commedia with a wicked humour. Rather than contemplating greatness and immortality, as Dante did, Brás Cubas reflects on his rather middling achievements, anecdotes brilliantly interwoven with hallucinatory digressions and philosophical meandering. Stake Colors in a Tall Field, by Carl Phillips, is a more demure ode to the passage of time, a rich and sensual book of poems that filters bucolic moments through retentiveness's nostalgic lens. How sharp that is at the end of this year, when memories of fifty-fifty the virtually miserable subway rides seem fit subjects for poetic attention.—Lauren Kane

Danez Smith. Photograph: Tabia Yapp. Courtesy of Graywolf Press.

How many ways tin I split 2020 in one-half? Recently I've been trying information technology, cataloguing my earlier-and-afters, counting the year's dissimilar selves by each major event. What a heavy year, to be remembered in fractures. The most obvious suspension happened in March, but there are other shifts that feel meaning, too—my virtual higher graduation, my soon-setting tenure equally an intern here at The Paris Review. Leaving college, for instance, meant I no longer spent most of my hours immersed in twentieth-century fiction, making my style through the canon. I pigeon into a more gimmicky excess: just this year did I finally read Sally Rooney's Normal People, Bryan Washington's Lot, and Cameron Awkward-Rich'southward Dispatch. And this year, too, I sought the condolement of old favorites: Richard Siken's State of war of the Foxes, Miranda July's No Ane Belongs Here More Than Y'all, Hilton Als's White Girls.

Starting at the Review was another shift. Though virtual, my time hither has immersed me in the deep waters of contemporary fiction. The by few months have felt like the most fruitful game of catch-up ever played, in which even transcribing interviews and filling in spreadsheets led me to some of my favorite reads of the year. Wasn't it over Zoom that I was compelled to read Bryan Washington's Memorial, a patient, deft novel that left me awash with tender feeling? Wasn't it for the Daily that I read Yaa Gyasi'southward Transcendent Kingdom, a meditation on personhood, and a confrontation with my ain tendency to hide, to burrow abroad, to withhold?

Each split, then, has come with a seeking feeling, and what I loved in the wake of June and Nov was work that felt immediate—an invocation of place, a celebration of who nosotros are, where we are. Nothing I read this twelvemonth carries that vital cadency more than Danez Smith's Homie. A collection by one of my favorite poets that includes "dogs!," one of my favorite poems, was bound to make this listing, simply Homie, an ode to Black and community, was everything I needed in a year defined by sadness, stress dreams, and skin hunger. The poems become weapons in "my poems" only plow to tributes in "acknowledgements" and are maybe both all the time. "this ain't about language," Smith says in the title poem, "but who linguistic communication holds."And if Homie centers me in the present, then Blackness Futures, edited by Kimberly Drew and Jenna Wortham, feels like existence held by a futurity self, one happier and more healed. Blackness Futures arrived earlier this calendar month as the universe's apology for the harshness of the year preceding—hither, have an album of beauty, of joy. The book is an immaculately edited collection of former and new favorite writers and artists encased in gorgeous sleeky pages I've pored over for hours. In the section titled "JOY," Hanif Abdurraqib appears, as does Danez Smith, as does Ziwe Fumudoh. And simply looking at it, the black hardback cover adorned with the iridescent block letters that read Blackness FUTURES, gives me happiness and promise, makes me feel inspired, excited, alive alive live—which I call up we need. —Langa Chinyoka

Karen Russell. Photo: Dan Militarist.

Within the first x pages of Joel Townsley Rogers's bonkers whodunit The Red Right Hand, reissued this year in Otto Penzler's American Mystery Classics serial, the surgeon Dr. Henry Riddle says he must "set the facts down for examination." On page 190, forty from the end, he declares, "I have got all the facts downward." To the character'south credit, his situation requires a bit of set-up. The job at hand is to explicate everything leading upwardly to the moment a Cadillac with a crazed devil of a out-of-stater behind the bike and a well-dressed dead human being in the passenger seat supposedly screamed past him on a narrow dirt road before disappearing. The merely problem is that Riddle never actually saw the automobile become by; he learned nearly the incident from the handful of other characters who populate that lonely stretch of New England countryside. Further, his ain automobile was blocking the route at the time the murderer allegedly passed. This is the kind of volume that, though brief, stretches its limbs like a cat in the August dominicus, padding slowly around the activeness, allowing just glimpses of the truth, all the while setting the reader's beatnik theories to boiling. It's a neat structural play tricks, ane that invites the creation of a mental corkboard cataloguing suspicions and coincidences. The exposition accumulates in drifts, never quite cohering into an easy solution, and the author fills out his corner of the Connecticut wood with a memorable bandage: the dorky, loquacious Postmaster Quelch; the sequestered surrealist Unistaire; the cranky retired Professor Adam MacComerou, who literally wrote the book on murder; and a portrait in negative of Corkscrew, the hitchhiker backside the bike, with his "scalloped hat," carmine eyes, and murderous cackle. By the fourth dimension the final pages swing by, snapping out of the expository slackness to evangelize a series of revelations that completely upend the story, the reader is liable to feel as though they've been taken for a ride in that Cadillac themselves. But it's well worth the cliffhanger; the desperate calculations and dogged attention I paid The Ruddy Correct Hand culminated in the most enjoyable reading experience of my year.

Elsewhere, I had trouble sticking to ane volume. Collections helped. I've greatly enjoyed my fourth dimension with Karen Russell's latest batch of stories, Orange Earth, which sparkles with the caliber of sentences most writers spend decades hoping to summon. In Russell'southward capable easily, I let reality dissolve around me like a meringue, blanketing myself instead in her rich, unmistakable voice. Each of the pieces I read in Lydia Davis's Essays One grounded me—a welcome feeling. Her essays are similar little pinned butterflies, pristinely preserved behind glass. In a year of painful ambiguity, information technology was a joy to rattle around inside the head of someone and then certain and articulate. And to the books I missed this time around: I'm deplorable. Ameliorate luck adjacent year. I know I'm certainly counting on information technology. —Brian Bribe

Elisa Gabbert. Photo: © Adalena Kavanagh.

I read Elisa Gabbert'south The Unreality of Memory in May, when we were all uncertain and pretty scared of what the pandemic was about to practise. The prescience of the book unnerved me in a way that heightened the reading. It's a wonderful collection of essays—I'll have to return to information technology at a different fourth dimension and run into how I respond.

"Since that moment," writes Zadie Smith in Intimations, "i form of crisis has collided with another." This book was one of the showtime sustained literary engagements to emerge from the crises of 2020—certainly it was the first that I read—and, though slight, information technology began the process of assembling our collective troubles into a denoting and familiar form. The volume isn't really a direct engagement with the pandemic or with the Blackness Lives Matter movement; rather, it'due south a setting of Smith'southward thoughts within the context of those realities. "Talking to yourself can be useful," she writes. "And writing ways being overheard."

But most often, rather than engage with the uncertainty of this yr, I allowed it to lead me back to familiar titles for comfort and comradeship. A lot of my reading this year has been rereading. Recently, though, I was consoled to find Richard Holloway's latest, Stories We Tell Ourselves, waiting for me on the chump. His is a reassuring vox. A one-time Bishop of Edinburgh who fell out of beloved with his church building and with God, he is practiced company on the page. I read him for his doubts and insecurities, for his willingness to admit both the starkness of life with God and the starkness of life without. Simply mostly I read him because I hear the accent and cadences of dwelling house in everything he writes. To borrow from Smith, I enjoy overhearing him talk to himself. —Robin Jones

Gina Apostol. Photo: Margarita Corporan.

This yr I read and watched and listened to the news in a way that would make my junior high civics teacher very proud, even yelling at the idiot box like my dad does. Only while the sensitive stoicism of reporters was a kind of absurd comfort, the feat or miracle of imagination, craftsmanship, and perseverance known as the novel was cause for 18-carat, happy hope. Early in the year I had my mind exploded past Gina Apostol's Insurrecto, the kind of book that makes i recollect, Yous can practise that? That is, tell one story from and then many divergent, imaginative points of view that the reader is left with a feeling of infinity, toss linear time to the winds, and talk frankly about the act of storytelling without sacrificing the joy of it. Yep, if you are Gina Apostol, you tin practise this, and it is beautiful. I read Insurrecto like some dogs destroy a stuffed toy; it was my favorite matter to practice. In other words, it expanded the possibilities of the form—only this isn't to discount the form's preexisting possibilities. I loved, besides, Brandon Taylor's classical ideal of a novel Real Life. Every scene, every dialogue, fits perfectly over a hall-of-famer first sentence ("It was cool evening in belatedly summer when Wallace, his begetter expressionless for several weeks, decided that he would meet his friends at the pier later all.")—delicate interlocking layers of story that build satisfyingly up and out around Wallace, his father, and his friends. In autumn, I settled into Claire Messud's essay drove Kant'due south Little Prussian Caput & Other Reasons Why I Write, the through line of which is that writing, in that information technology enables 1 human to understand the feel of some other, is magic. Each successful judgement, Messud asserts, is "a seizing of ability away from fear and desire." Of class she's correct. In this year that has seemed like it might really end all years, books are medicine for the human being status. —Jane Breakell

N. Scott Momaday. Photo: Darren Vigil Gray. Courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers.

Because the first half of 2020 was my last semester of undergrad, much of my reading this twelvemonth was retrospective. Michel Foucault, Saint Augustine, and Carlos Monsiváis acted equally the theoretical lenses for my school piece of work while Mexican films, Graham Greene, and Flannery O'Connor formed the meat of my enquiry, all while I inhaled Paradise Lost, John Donne, and Edward Said through Zoom classes afterwards quarantine began. Upon graduating, I still plant myself looking back in my reading. I reread Between the World and Me and The Audio and the Fury while checking out Northanger Abbey, Sula, Tommy Orange's There There, and Kiese Laymon'south Heavy for the commencement time; I institute myself floored by each one. But upon joining The Paris Review, I immediately felt my reading horizons expand with the plethora of new books constantly being thrown my manner. As I've discussed before, F*ckface, past Leah Hampton, fabricated me ill with longing for the Appalachia of my undergrad, in all its humor and tragedy. Later on, César Aira's Artforum (translated by Katherine Silver) drew me back into the theory to which I dedicated so much time last year, but all with a smooth, smart satire that made for an effortless read and an intellectual earworm at the same fourth dimension.

Most recently, I finished North. Scott Momaday'southward latest drove of poems, The Death of Sitting Bear, which, frankly, took me some time to process and appreciate. It'south a fragile book that draws from a tradition dynamically opposed to the hyperintricate wordplay and referentiality of the contemporary verse with which I most oftentimes engage. Instead, The Death of Sitting Bear loads its lines with a heritage and history that commune with the body and the soil of the planet, invoking a sort of contemplation that points away from the bare bones of language and into the lifeblood that is memory. In particular, Function III of the book, which recounts the life of Sitting Conduct, contextualizes the collection equally an exercise in remembrance.

Now I've started Yaa Gyasi'southward excellent novel Transcendent Kingdom, and I observe myself—after a year in which much of my reading was slow and distracted—fully enthralled past Gifty'south narrative and all the intricacies of how she relates to the world. As I extend myself into more gimmicky works than those of my undergrad, I find it all pleasantly circular. Every book I read feeds dorsum into what I've read before and how I'll read what's side by side. That's growth. And even if it's stunted by the insanity of 2020, I recall that's still something to exist proud of. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

Jenny Erpenbeck. Photo: Nina Subin.

This has been a foreign year for reading, and I am not certain what I will remember nearly when I await back on 2020, or even what I was looking for in the books I read when I could pull myself abroad from the news. Machado de Assis's Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas, translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson, brought me more than joy than annihilation else I read this year; a sparkling stiletto of a book, its deftness and light touch on leave you open to its blade. Magda Szabó's Abigail, translated by Len Rix, came out in January, but I returned to it more than once as the twelvemonth went downhill—not simply for a retreat into the past and a foreign land, simply as well for its simplicity, the uncomplicated black and white of its morality. Azadi, a collection of very recent essays past Arundhati Roy, was the one that shook me, a reminder that while later a disaster nosotros have the chance to amend on what was there earlier, doing so is an effort that requires piece of work and imagination. But ultimately, in this yr of storms, the book that gave me what I needed, fifty-fifty if it wasn't something I knew to await for, was Jenny Erpenbeck's Not a Novel, translated by Kurt Beals. Perchance because it is a memoir, in which ultimately the center is one person and that person's relationship with herself, information technology felt to me similar an centre-of-the-hurricane volume: aware of what has merely passed, aware that more is on the horizon, but standing in the momentary stillness and reassembling itself to face any is coming side by side. —Hasan Altaf

Dan Gemeinhart. Photo: Kathryn Denelle Stevens.

Every bit the pandemic fell heavy upon u.s. this spring, I thought, Finally, the opportunity has arrived to read those long books for which life rarely affords the fourth dimension. I came upwards with a scheme: I would alternate between two series. And then over the past several months, I tackled Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan novels, cleansing my encephalon after each Ferrante with one of Rachel Cusk'due south Outline trilogy books. I am unduly proud to written report that just this week, I finished my Herculean chore and take now read seven books! All by myself! I found Ferrante utterly mesmerizing, and Lena and Lila were essential company during these dark months. I must admit less enthusiasm virtually Cusk's cast of unpleasant characters, though I e'er constitute myself grateful for the kind of replacement consciousness that Cusk provides.

I read a few other books this yr, simply I will recommend only 1 more at this juncture: The Remarkable Journey of Coyote Sunrise, a middle-grade novel by Dan Gemeinhart, which my wife, my daughter, and I read aloud together before bedtime over a few weeks. It is, truly, an incredible book, the harrowing and funny story of a daughter and her father, who, post-obit the death of the daughter's female parent and 2 sisters, take to the open route and alive in a modified schoolhouse bus. The volume is total of misadventures, including but not express to an interval in which a caprine animal becomes a boyfriend passenger. Near the end of the book, at its emotional climax, my wife and I found ourselves subject to a veritable orgasm of sweet sorrow—the two of us cried mightily with our bewildered girl between u.s.a.. If you would similar to have your heart's guts scraped out and replaced with … amend guts, I highly recommend this book, which volition indeed get out you purified and inverse. Despite this clarification, I assure you it is a nifty family read. —Craig Morgan Teicher

Desus Nice and The Kid Mero. Photo: Greg Endries / Showtime.

I used to love a product. Strength-feeding my gentleman New York soundstage classics like Guys and Dolls near the beginning of quarantine reminded me that reality never had a take chances. In that location's gotta be lights and music, dance and costumes. I wanted the correct book for 2020 to come leaping through the air bathed in spotlight, to land in my easily, sing a petty tune, and open things right upwards for me. Only in that location'south a reason I strayed from musical theater: existent life doesn't follow such a tidy chiliad jeté. Many books arrived when I needed them this yr, nigh none of them new or undiscovered. I read Barbarian Days, William Finnegan'southward Pulitzer Prize–winning surf memoir, which reminded me that even New Yorkers can experience modest beside the ocean and that many, many men earlier me have married the sea. I read Joan Didion's The White Anthology, which can indeed be read as social criticism on whiteness, though that is not the whiteness to which the title refers. I read Milkman on the recommendation of an advisory editor for this mag. It was so stupefyingly original and sharp that I wanted it to win the Booker all over again. I bought several magazines off of the newsstand. The New Yorker e'er has something—how is that? I lingered on Vanity Off-white'south beautiful September 2020 issue, which was guest edited by Ta-Nehisi Coates, and its December 2020 issue, which features a galvanizing interview with Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a woman so smart she need only wash her face in the morning to set the patriarchy quaking. Then at that place were Desus and Mero. They've written a volume, God-Level Knowledge Darts: Life Lessons from the Bronx, and I recommend it, but everything this duo touches turns to comedy gold. The gents go past Desus Squeamish and The Kid Mero, friends from the Bronx who tell stories in a way that made me rethink comedy and the 2 railroad train. Frequently Desus leads the narrative while Mero gets into grapheme, but in a way that is so subtle information technology resists assay, transcends being a bit, and gets me laughing till I'm physically exhausted on days I take no business concern even cracking a smile. I'chiliad non proverb it'due south a vaccine; all I'm saying is I take the feeling that Desus and Mero are peeling 2020 off the footing, 1 scalding pepperoni piece at a time. —Julia Berick

Jill Lepore. Photograph: Stephanie Mitchell / Harvard University.

At the start of the twelvemonth, filled with big plans for my new self, I began a listing in the back of my journal with small annotations on each book I read. Next time I have to write nigh my favorite books of the yr, I thought, I'll exist prepared. That list, of form, ends abruptly in March. An addiction to breaking news alerts frayed my attention bridge so completely that the thought of finishing a novel became laughable. I was unable to get lost in fictional worlds when the existent one had become so surreal. Reading was the thing that had one time brought me the most joy, but for much of this pandemic, not to mention that moment when it felt like we might be on the brink of civil war, not to mention the months when America's fundamental white supremacy rushed to the fore, I could not pick upwardly a book. When it came time once again (how?) to put this list together, I thought seriously about simply writing in, "I was supposed to read books this twelvemonth?!?!" But the truth is, despite myself, I did. Garth Greenwell'southward Cleanness, which I read dorsum when I still knew how, gives the act of sex the attention it has always deserved from a swell novelist, unfurling across whole chapters what unremarkably happens in the spring cutting. Anna Burns's Little Constructions, which I was reading in mid-March, turns the darkness of humanity into the best joke you've e'er heard. Her morbid surrealism is perfect for our times, merely in this book all the characters take essentially the same name, and when my mind went, and so did my power to follow hers. Lily King's Writers and Lovers and Kate Reed Footling's True Story were able to remind me of the pleasure of reading when I was certain I had lost it forever. Both are that surprisingly hard-to-observe gem, books I will stay up all night for, books that volition make me forget where I am, and yet the sentences are likewise nice, and the mind behind them very abrupt. For a long time the only thing I could read, and very slowly, was Jill Lepore'south brilliant These Truths, a history of America I badly needed, and near unfairly, overwhelmingly, eloquently told. Now, finally able to read normally over again, I find myself immersed in Vigdis Hjorth'due south Will and Testament, the perfect book for a cold wintertime calendar month in which all you want to think about are, please, just let me focus here, the small interpersonal dramas of a dysfunctional family unit. —Nadja Spiegelman

Joy Harjo. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Equally history is being fabricated, information technology feels of import to also admit history built—and this yr, that (re)construction of our nation's literary past came in the guise of ii remarkable anthologies: When the Calorie-free of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through, a collection of Native nations poesy edited by Joy Harjo with LeAnne Howe and Jennifer Elise Foerster, and African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle and Vocal, edited by Kevin Immature. Of course, brilliant new work was published this year, and for this reader the bleakest of years was made better by encountering Natalie Diaz'southward Postcolonial Dear Poem, Cathy Park Hong's Pocket-size Feelings, Gabriel Crash-land's Everywhere You Don't Vest, Diane Cook's The New Wilderness, and Ayad Akhtar's Homeland Elegies, to name a few authors whose writing grabbed me firmly past the shoulders. But to step out of the news cycle (and I include book press in that), to contextualize today past looking across the contemporary moment'southward triumphs and injustices (an accounting slanted steep toward the latter this twelvemonth), is alike to opening a door from a small room into an infinitely larger 1. I found myself exploring these histories with the guidance of generous, skillful editors—but also feeling sufficiently equipped by their thoughtful methodologies that I could develop my own path through. This idiosyncratic wayfinding led me to remarkable line and language, and each page affirmed the injustice and exclusion of before versions of American poetic history. But I found myself perchance most drawn to the narratives herein, gripped past their authorisation. Here, as well, was triumph and injustice, both inextricably bound to what we call America. Here was history and a version of possibility unique to this country. And here, within the struggle, was promise. As Peter Blue Cloud's "Rattle" begins: "When a new world is built-in, the one-time / turns inside out, to cleanse / and prepare for a new first." —Emily Nemens

Source: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2020/12/18/the-paris-review-staffs-favorite-books-of-2020/

0 Response to "How to Remain Focused Reading Books Paris Review"

Post a Comment